There are plenty of things in this world that we don’t understand: modern art, New Yorker cartoons, physics. But domains aren’t one of them. In fact, we know the anatomy of an address bar like the back of our hands, so we’re gonna break it down for you (because we don’t want it ending up on the list of things you don’t understand).

The 4 Parts of an Address Bar

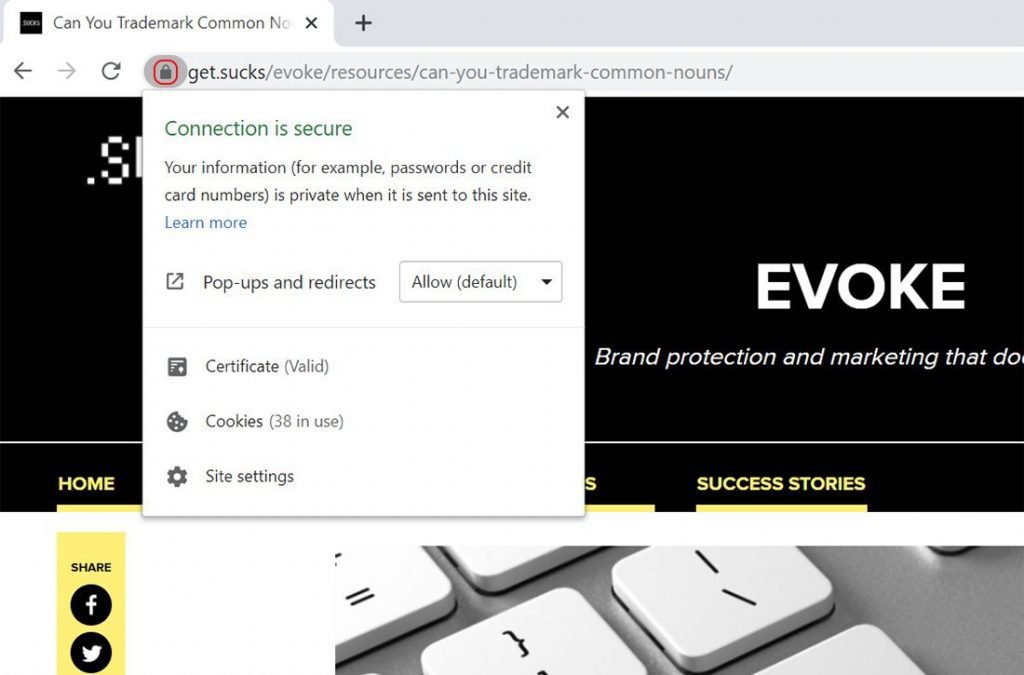

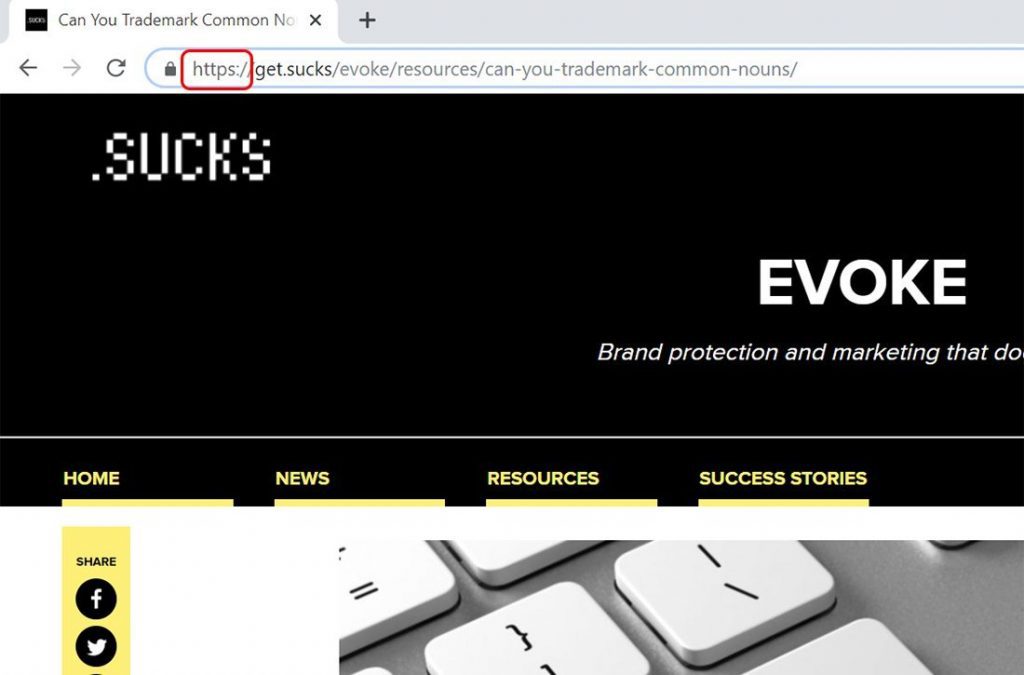

1. SSL Certificates

See the little lock icon on the leftmost side of your URL? That’s indicative of an SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) certificate, a type of security technology that makes a connection between two things: domains, servers or hosts, and organizational identities and locations.

When you see the lock, it means communication between a website and a web server has been authenticated and encrypted. In other words, the personal details you share with that website—like your home address, password or credit card details—are protected against malicious parties, like hackers or identity thieves.

2. Application Protocols

The application protocol, also known as the scheme, indicates how a site collects, transfers and manages data. You’ve probably seen a bunch of different types (such as HTTP, HTTPS, FTP and mailto) in your address bar at some point, and that’s because each serves a different purpose. For example, FTP is for transferring files and mailto is for transferring emails.

Most commonly, sites use either HTTP (HyperText Transfer Protocol) or HTTPS protocols, which allow web browsers to communicate with web servers—it’s what helps process a request (e.g. typing a website address) into data (e.g. webpage content). If the website owner has installed an SSL certificate, the HTTP will become HTTPS; the “s” stands for “secure” and is intended to let users know that there is an extra level of protection. If you need to provide any sort of personal information—whether it’s to purchase a product from an e-commerce site or to create a user account—make sure an “s” appears at the end of the HTTP protocol.

3. Domains

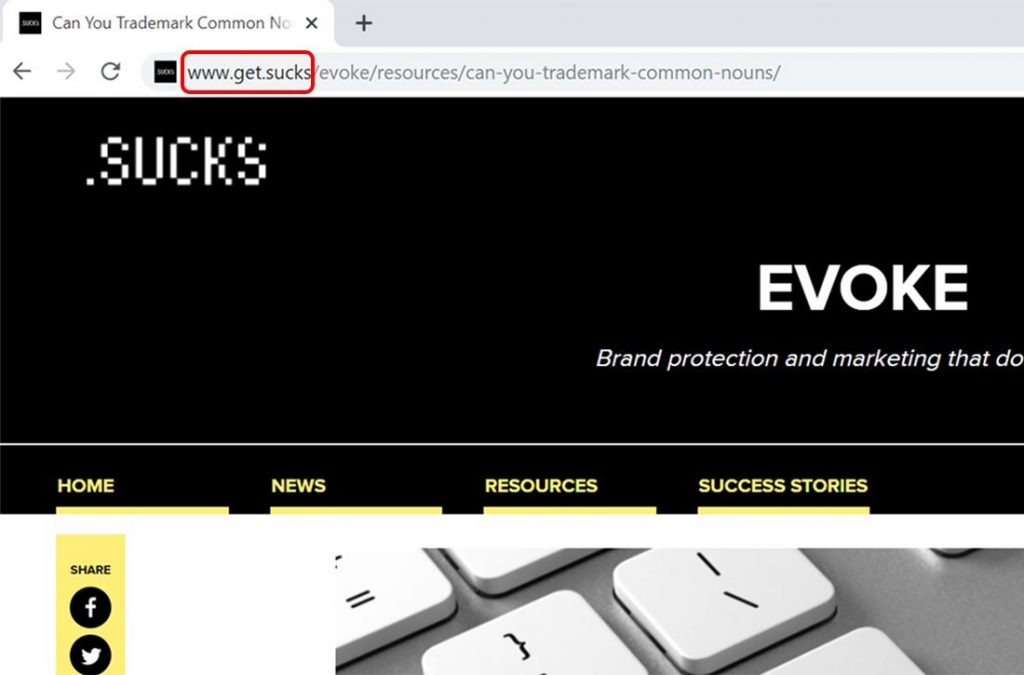

Subdomains

The “www” in your

address bar is one of many available subdomains, which help to organize

a website. For example, a fashion blogger may host their content at

www.mystyle.com, but may also use shop.mystyle.com to direct readers to

their online store. Subdomains are not case sensitive—your browser will

be able to direct you to the right place regardless of how they’ve been

typed into an address bar. And in some cases, they may not be needed (or

appear in an address bar) at all. You can get to our site simply by

typing “get.sucks”.

Second-Level Domains

In

URLs like www.get.sucks, www.google.com and www.amazon.ca, “get”,

“google” and “amazon” are known as second-level domains. These are

unique to each site, and usually provide information about the webpage

users will land on after pressing enter. Typically, second-level domains

contain the name of a business or product (swiffer.com), the name of a

public figure or celebrity (beyonce.com), or a message about the site

owner’s goal/purpose (savetheplanet.com).

Top-Level Domains

In

an address bar, the second-level domain (i.e. what comes before “the

dot”) is followed by what’s known as a top-level domain (TLD). While

there used to be only a few available for use (for example, .com, .org

and .net), the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers

eventually had to introduce others.

These new generic top-level domains (ngTLDs), like .SUCKS, .university, .fashion and .coffee have become increasingly popular, and we’ve covered them pretty extensively in the past. Here are some resources for anyone who might have missed it:

- All About ngTLDs: Why Are They Valuable and Who Decides What’s

- Beyond .com: What Else You Should Know About Domains

- What, Why, Where, How? Building Out Your ngTLD Strategy

- A Changing of the Guard: How Will ngTLDs Impact SEO

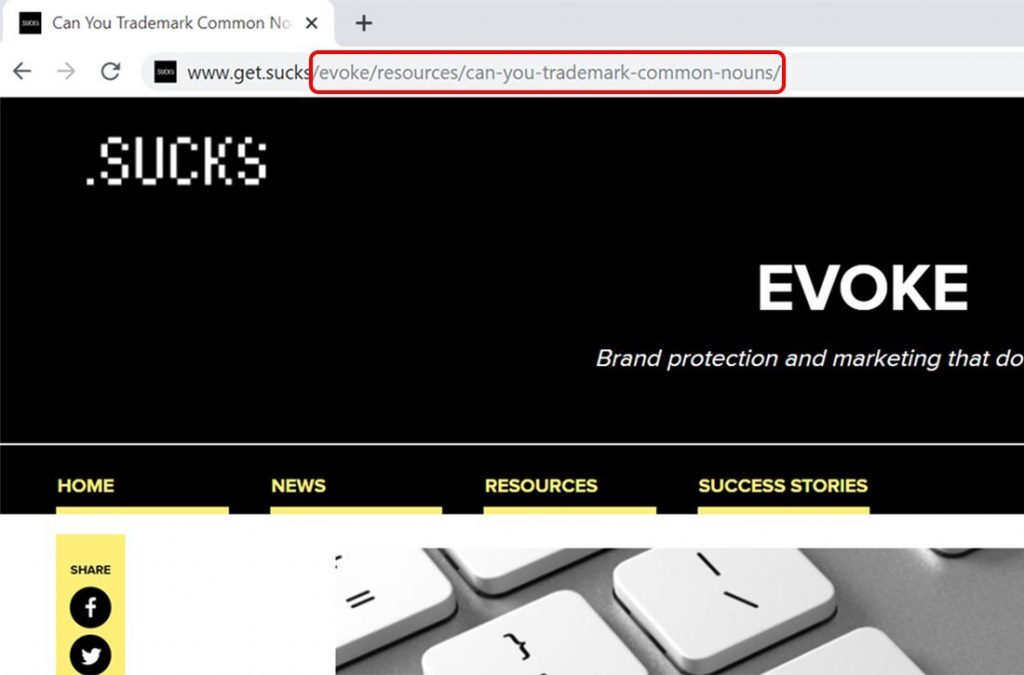

As you dive deeper and deeper into a website, you’ll see slashes, dashes and keywords start to populate your address bar. This segment of the URL, called a path or filename, denotes which folder, file or hyperlink you’re currently looking at.

Unlike second-level domains and TLDs, the path/filename iscase sensitive, so be careful if you’re typing these in character by character instead of copy and pasting. If no path is specified, you will automatically be taken to the “index” or homepage of that particular site.

The Takeaway

There’s more to an address bar than meets the eye, and there are three particularly important things for website owners and users to know: (1) how all the pieces of a URL/domain name fit together, (2) the different levels of security that are available and (3) what each of these elements may signal to visitors and consumers. Once you’ve figured that out, you can experiment with protocols and TLDs to find what’s best for you and your followers, readers and customers.

See what other brands have done with an ngTLD like .SUCKS, or find a domain that speaks to you—and your target audience.

Photo Credits: Shutterstock / ZoFot